Dear Mr Dickens,

I write to you once again, in dire need of answers.

Having finished David Copperfield with immense delight, I naturally proceeded, without rest or restraint, to another of your mammoths, Bleak House. And what an opening it is. London swallowed by fog, the air thick with implication. I know in my bones that I shall love this book dearly as the other three I have had the pleasure of inhabiting.

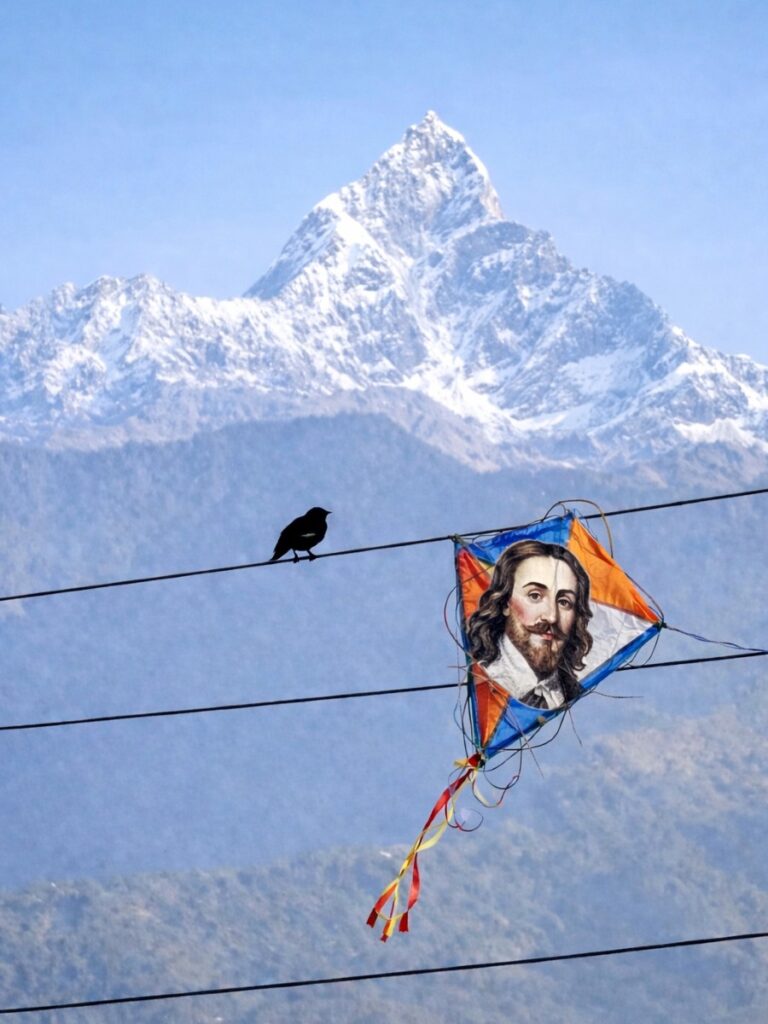

Yet, much like Mr Dick himself who cannot keep King Charles the First’s head from rolling inconveniently in and out of his thoughts, I find that I cannot proceed just yet. Mr Dick has followed me here. Worse still, he has taken to flying his kite with that unfortunate royal head attached, sending it skyward to the peak of Machhapuchhre, to the clouds where it seems to belong.

And if I may digress: before David Copperfield, I had already survived a flurry of rolling heads from the bloody guillotine of A Tale of Two Cities straight into Mr Dick’s eccentric mind. How did King Charles the First’s head lodge itself inside him, unresolved? I cannot express how much aristocratic decapitation has made me quite dizzy this winter. And yet, strangely enough, these rolling heads have left my dark mornings with pure comedic delight.

Mr Dick is one of the most beloved eccentric characters I have ever encountered, and I carry a terrible itch to write about him, if only to set my mind at ease. Before I do so, I must ask you, dear author, how did you come upon such a singular creation?

“Every day of his life he had a long sitting at the Memorial, which never made the least progress, however hard he laboured; for King Charles the First always strayed into it, sooner or later, and then it was thrown aside, and another one begun. The patience and hope with which he bore these perpetual disappointments, the mild perception he had that there was something wrong about King Charles the First, the feeble efforts he made to keep him out, and the certainty with which he came in and tumbled the Memorial all out of shape, made a deep impression on me.

What Mr Dick supposed would come of the Memorial, if it were completed; where he thought it was to go; or what it was to do; he knew no more than anybody else, I believe. Nor was it at all necessary that he should trouble himself with such questions; for if anything were certain under the sun, it was that the Memorial never would be finished.”

There is something deeply moving in Mr Dick’s way of thinking. He appears fragile to the world, yet he holds a curious wisdom that troubling thoughts cannot be destroyed, only given air. His kite feels like madness and release all at once. I cannot help seeing him now alongside Dr Strong. One patiently pinning words down in his Dictionary, the other cheerfully letting thoughts loose into the sky. I think of kite-flying itself as an act that suggests freedom yet remains obedient to a string. It rises only by negotiating resistance. Where I now live, kites are flown during Makar Sankranti to mark the sun’s turning and to greet Surya. It is not to conquer the sky but to converse with it. Perhaps Mr Dick understands this instinctively; that thought, like a kite, grows dangerous when hoarded, and humane when given air? I suppose that freedom is never an escape, only a more honest bond.

Perhaps every novelist needs at least one character who ignores the plot and grants the author permission to accept that life does not always submit to explanation? Enlighten me if you may?

And one final question if I may. Did Mr Dick arrive fully formed, or did he grow under your pen insisting that he be allowed to remain?

I ask not merely as a reader, but as one who suspects that Mr Dick understands something essential about the human condition that more sensible persons have entirely overlooked.

With admiration,

A string tangled somewhere above the clouds

…while a certain Mr Dick refuses to leave.