Wild heads of vivid yellow, orange and gold make the shape of loveliness. Dotted with lilac and violet, the starkness of colour brings to life a change of seasons. Untamed, the petite petals perfume wild intentions of overriding the green, unveiling the silence of a Himalayan autumn that is at once a lingering green and gold.

Autumn with her usual flair of letting go doesn’t quite make its appearance here. Preceding the months of October, monsoon overwhelmed summer by shielding the sun’s rays, drenching the land with rolls of mist, heavy clouds and relentless rain, hence leaving the land soaked and fertile. But the heat of the sun stood its ground blazing when the time came for monsoon to pass over the peaks of the Himalayas. Weeks of intense blue without a trace of white, painted the canvas of the skies nude. The sudden absence of cloud magnified the glowing ball of fire and within weeks of what memory could recall of overflowing gushing water from every creak and crevice, the ground dried up as quickly as the water filled up the water banks in a weekly episode. Within a matter of weeks, the landscape transformed from a gushing stream to a quiet trickle, from muddy terrains to dried dusty lanes, from serene green stalks to golden heads of paddy. The incredible transformation of the landscape within a short span of time was spell bounding.

As November arrives, slumber is punctured by two significant festivals in Nepal where the celebration would typically take rein of the entire country for weeks in the pre-Covid era. The economy would halt its grinding wheels and cities would be deserted. Dahsain, the culmination of Navaratri, a 10-day long festival brings alive again the essence of the epic and beloved Ramayana during Treta Yuga, marking the triumph of Rama over Ravana in Sri Lanka. And in tandem, Dahsain also signifies the slaying of Mahishasura by Durga, who was immortal to men but his ego ultimately brought about his fall – a reminder to the devotee to be rid of his/her ego which is an obstacle to enlightenment.

Thereafter, upon recovering from the lengthy celebration, Diwali, the festival of lights appears around the bend in a smatter of weeks. Commonly known as Tihar in Nepal, the 5-day celebration brings about the observation of light over darkness and of clarity over ignorance – the unveiling of a cloudy perception and of emotion that often blinds the truth. It kicks off with worshipping the crows, dogs and cows as a recognition of the importance of their symbiotic relationship with humans. The crows are messengers of death, the dogs guard the gates of the netherworld and the cows are a vital source of nourishment. Intertwined with welcoming Laxmi, the goddess of wealth, there is much prosperity to celebrate for. However, perhaps the most captivating thread of Tihar is the celebration of kinship between sisterhood and brotherhood. Sisterly blessings are given to brothers by painting a strip of colourful tika on their foreheads and love is showered upon them in garlands of marigolds. In return, brothers renew their faith in protecting their sisters’ well-being.

In this timely event, it is an opportunity to reflect upon the beauty of sisterhood. Birthed in November, my elder sister has always been a stronghold for unprecedented support, sensibility, endurance and love, a quality of the most beautiful kind a human can endow on another. She is a flame of the unquenchable that would flicker and sputter and vanquish not until a deed said is a deed done. A female warrior in her own right, she carries the weight of responsibility urgently but always has time to share her wholehearted presence with whom she speaks to. I recalled once upon a time when I made a call to my brother who was aroused from sleep, he dazedly enquired which sister he was talking to and I said the less responsible one. It probably took him less time to realise who the caller was than the announcement of my name. Whilst differences there are in our view of things and life choices, she would nevertheless uphold space for each other’s creativity in life because celebrating and respecting differences can be ultimately more beautiful. The privilege of sisterhood is knowing that although her presence is missed, her intangible absence is always felt and cherished for distance is only a physical barrier whilst an ocean of a heart is everlasting. Presently in our middle ages with silver sprouts flowing from our crowns, looking back through our journeys perforated with intersections of coming and going, there has been little exchange of words – words of appreciation, of gratuity and of love. There seems to be more comfort for me in written words for there is a threshold for thought and clarity to speak from the heart and mind. Perhaps it also takes more courage to express an emotion or a sentiment vocally but here I am, imagining that beautiful tika painted on her forehead.

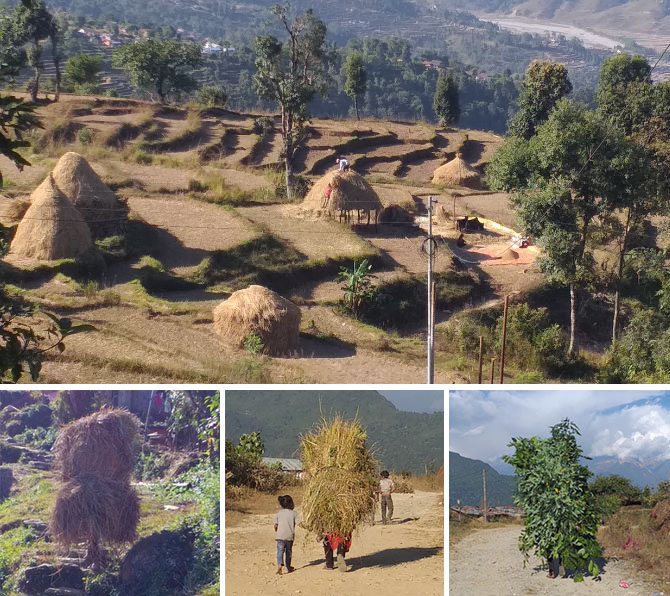

Autumn also marks the season of harvesting paddy, a lengthy and laborious, but rewarding process that transmutes an incredible landscape from April to November. And then allowing time for recuperation of the land over winter. Families gather to reap their labour of success and this is truly another celebration in itself. Once the ground is dry and the grains are full of yellow hulls and the stalks of the plant are slightly bent, the stalks are then cut off with a sickle. They are laid out to dry in the sun for 3 to 4 days. Then the stalks are threshed to separate the grains. Finally, milling takes place to remove the husk, bran layer and germ. Whilst the humans enjoy the rice, the reared animals consume the dried stalks. Prior to the feed, the stalks are crushed by the trampling hooves of buffaloes to break the fibres down and quicken the drying process. The dried straw would then be stored near the sheds of the milk-giving animals as winter feed and these cuboid-conical stacks inevitably becomes a common winter landmark.

However, transporting dried straw requires strong legs, a copious amount of energy and pure love. The milk-giving animals are after all an extension of the farmer’s family. At first sight, a walking bale of either wild grass or paddy straw brings sight of amusement. With what look like popped-out legs from the rear view, the bales animate a surreal picture of Astam’s singular lane occasionally dotted with a gathering of bleating goats or a grumpy buffalo. The scene may add to a colourful tourist album but the reality involves sheer hard work and dedication to animal rearing. Wild grass, arranged in long, thick and compact bundles is carried up and down the terraces and unloaded in the bamboo sheds of these mammals. With no availability of grazing land and with challenging steep terrain, the village’s buffaloes, cows and goats feed are brought to them daily. But their hard work pays off in the quality of milk that is metabolised from freshly cut chlorophyll sun-drenched grass.

Meanwhile, Ganesh awaits anxiously for the continuation of work on the Shala. Thankfully with the return of the Jumla men, work has finally continued after its foundations were built almost a year ago. The first slice of the earth wall appeared as the morning rays warmed the land and the familiar resounding of sand, gravel, clay and cement are rammed into rock. The men’s rhythm of strength and enthusiasm fused with swift strikes of wild grass cutting by Ama-of-the-land by the edge of the forest brings out a tender companionship between them. A tenacious spirit with a big heart, Ama treats every one of the Jumla men as her son, always extending the warmth of her humble home to all of them.

It has been a towering year of shift, of adjustment, of assimilation, of transformation. And a truly valuable year in reflecting upon our decisions and actions in the midst of this rugged terrain. Akin to the hardness of the mountains and softness of the snowscapes, there comes an invitation of a cyclical play of hardships and heartships. Amidst fragmentation and displacement in this often challenging equation of life, perhaps the question begs to remind the keep for clarity to keep this journey going. As Anne Gilchrist fittingly shares, our illusions of finitude and fragmentation is a self-imposed prison of smallness, from which we are liberated only when we learn to see the interconnected wholeness:

“…Underneath your feet, if you go far enough, you come to blue sky and stars again; that there really is no “down” for the world, but only in every direction an “up.” And that this is an all-embracing truth…”

Against the cosmic landscape, our life span is not a drama complete in itself, but only as a brief interlude in the infinite universe of stardust. Where nothing ever truly dies – only a change in the structure of the atom and transformation of energy and matter of the pulsating metabolic black.

Note: The illustration above is Laniakea – a galactic supercluster comprising about 100,000 galaxies. The red dot seen is our Milky Way.

Credit NASA.

IiLing

31 Dec 2020Ahh hubby is reading!🤓

IiLing

31 Dec 2020🙏

AGM

31 Dec 2020😍

Pa

27 Nov 2020How profound your feelings and observations sisterly love.

I have always said that going back in our family ( I suppose with many Asian families as well) the first born carries that burden,that responsibility and to me that honour

Ganesh

26 Nov 2020Very good read! Thank you🙏🏻