“You cannot swim for new horizons until you have courage to lose sight of the shore.”

William Faulkner

Just as we thought the adventure had come to an end, we found ourselves in a jeep taking us home on a road that was not a road.

We had thighs and knees, jittered and jellied, calves hardened like sculptures. Now our insides were shaken like a snow globe, disoriented for 2 hours, thumped and bumped against all sides of the spring-less vehicle. We feared Bola, our small-framed porter who had decided to hitch a ride home on the roof of the jeep was thrown off at some point. Miraculously, the jeep stops and we watch his legs slide down the edge to the ground. There he was, intact, wearing a grin on his face, obviously happy to be home. The driver continued as we passed Ghalel, and headed towards Lumre. His mobile rings and he answers it, chatting animatedly with one hand on the steering wheel driving through undefined dark terrain while we continue tossing around like a chickpea trapped in a salad spinner.

Exhausted in body, dazed in mind, and finally with a grateful cup of coffee, I try to make sense of what had happened in the last 72 hours of our lives. Like most adventures, we come away looking at life anew and with a fresh perspective. There is much for contemplation. There is more gratitude and graciousness. There is more comfort in our beds, more nourishing foods, more abundance, and so much more beauty in all the little things we have and do in our daily lives.

On that chilled morning, we rose from bed blinking into the half-light and the long shadows of dawn. By 6 a.m., we were out the door and into the waiting jeep of Herke, who sat behind the wheel, his face drawn by the weathered lines of the land. He ferried us through the sleeping villages, up the undulating road that twisted and wound its way toward the waiting trailhead at Dhampus. It was there, in the stillness, that we first placed our feet upon the path that would lead us onward and upward, to Pothana and beyond.

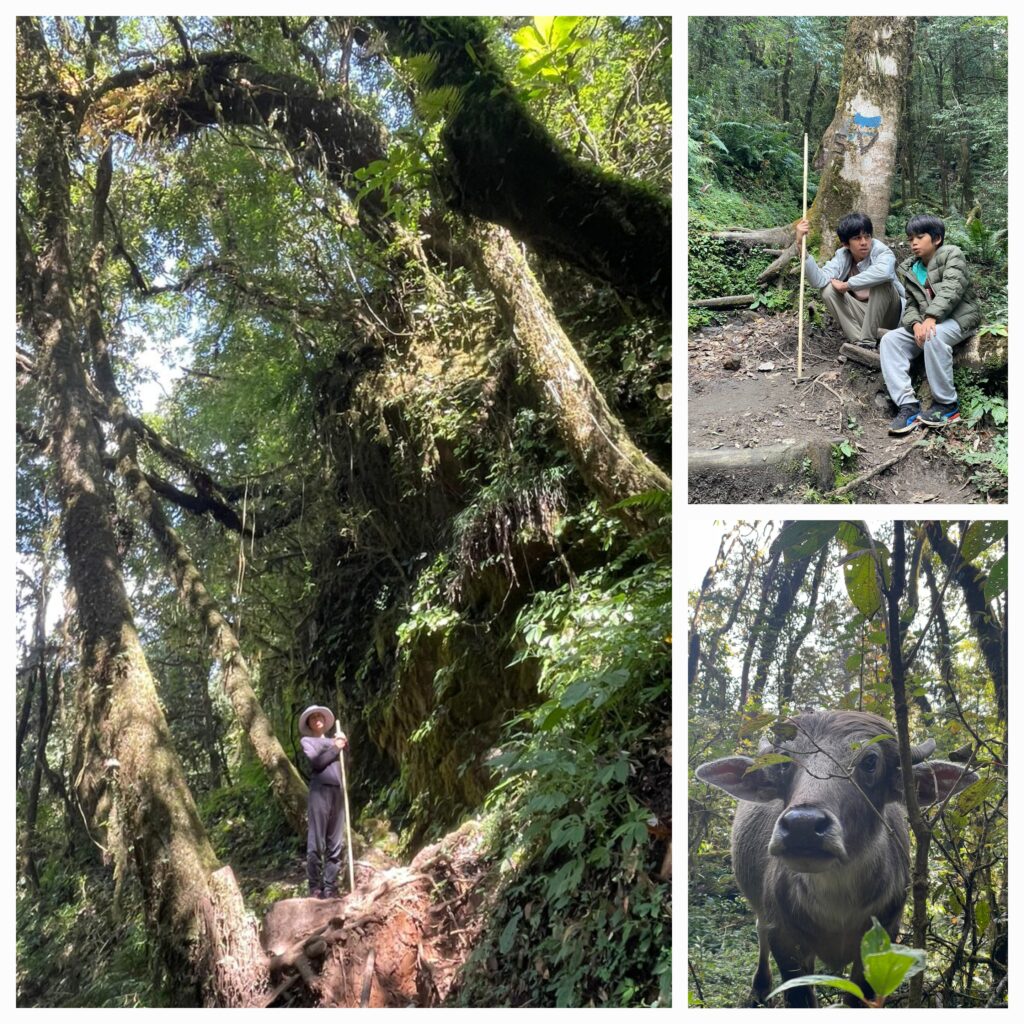

We set off, our forms but dark figures against the pearl-gray mist. The earth gave beneath our feet, thick and muddy in some places, firm and rock-bound in others. Slowly, we passed through a world that seemed to change with each step. Behind us, the sun rose higher, coaxing a soft amber light from the paddy terraces and villages below. But as we climbed, the landscape began to shift. The terraces dissolved into ancient forests, and we found ourselves enveloped by trees that loomed like green giants, their broad boughs stretching overhead, cradling sunlight in cupped leaves.

And the silence, a silence so thick it was not of this world. Only occasionally would it break by bird calls or low snorting wild buffaloes. And so we walked, awed and dwarfed, feeling for all the world like Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit in some hidden, forgotten kingdom.

The path led us deeper, winding like a thread into lush rhododendrons, oaks, birch – all soaring toward brighter light. And beneath them, we walked, our heads bent, our steps breaking the silence with the brittle snap of twigs. I could feel the earth, cool and rich and alive with age, and I thought, yes, this is how I wish to tread the world: light and humbled by its beauty.

The trail wound ever onward, climbing in its slow, meandering way from hill to mountain, inching skyward for another five hours until we arrived at last in Forest Camp, the air cooler now, filled with earthy scent. Forest Camp for the boys was a world of the four-footed and the feathered – the grunts of wild buffaloes, the bellowing of oxen, the song of chickens and roosters, and the promise of instant noodles. Here, under a small clearing, we looked out and saw them once again: the distant snowcapped mountains.

Ever wondered what the differences are between a hill and a mountain? Surprisingly, there are no absolute definitions. Here are a few variations I discovered. Mountains and hills are natural mounds of earth created by faulting and wind erosion hence have a higher altitude and elevation. If you can get to the top in a day, it is a hill. If it takes longer, it is a mountain. If it has deer, it is a hill. If it has mountain goats and grizzly bears, it is a mountain. If Astam was plucked and relocated in the flat plains of the Savannah, then Astam is a mountain. In Nepal, Astam is resolutely a hill. And yet, for all the definitions, for all the attempts to draw lines in the sky, the truth remains evasive.

We meandered through villages and guesthouses and quickly realised the shape of blue tin roofs replacing the traditional slate roofs of many old dwellings, would appear and disappear frequently along the trek. Gone were the days of teahouses sheltered by tattered tarpaulin which served only sweet sticky masala chai. Old homes have become tourist establishments to make trekking more comforting, providing food and drink at frequent intervals. They mark resting points and restroom stops. There was no real need to empty your bladder behind a bush any more and fear that a curious creature would hop or slither into your pants as you pulled them up. These treks are dotted with WiFi connection letting you feed your Instagram as you go along. Trekking in the 21st century, like all things, is powered by money and GPS. But what remains left to be seen are the small-framed powerhouse Nepali porters. They often carry loads twice their own body weight and still get to the summit of your destination while you huff and puff halfway through the mountain.

We spent our second night at High Camp 3600m above sea level. It was a terrain where water cost more than food and lodging, and the act of teeth brushing was vexatious. Left with frozen teeth and fingers, the boys were excused from it. On the flip side, this meant that the peak of Machhapuchhre had never been seen or felt so close and intimate. A sacred mountain in Nepal, it is believed to be the abode of Lord Shiva hence the prohibition for mountaineers to summit. Rumours have it that a British group attempted it in the past before the ban in 1962 but in a gentlemanly fashion, turned back 150m short of reaching its peak as a promise to King Mahendra.

Looking back, that night on the plateau of Mardi Himal was my far-reaching moment—the kind of moment that takes hold of you, shakes you, and doesn’t let go. The sky above was vast, crystalline, an endless expanse as if the universe had opened itself wide. It felt unreal watching everything we knew about this world twinkling above only to be struck by the sudden, terrifying knowledge that we truly know nothing.

It was a night when we could see the faint band of light, our Milky Way, stretched across the great, dark vault, a soft, glowing scar on the black canvas of the universe. We stood there, heads tilted back, necks twisted like owls, as if trying to drink in the immensity of it all—the jagged ridges in silhouette, the ghostly chalk-white bulk of the Annapurna rising sharply against the western sky, the Moon, planets, stars, constellations, comets, meteors, galaxies, and all the names we give, like feeble attempts to tame something so boundless. It was a night that was loud and silent all at once. A night that tore open the veil and showed the terrifying, beautiful truth of existence.

In that moment, I felt my fragility, my smallness, and the crushing weight of time, stretching back over 13.8 billion years, a span so immense it defies understanding from my puny brain. And yet, there we stood, a mere collection of stardust, spun into this strange, miraculous form, staring out at the yawning emptiness, the nothingness. It was a glimpse of eternity. A face of infinity. A cosmic mush. Vast and indifferent, yet somehow alive. That night spoke an ancient language older than the stars themselves.

The phone alarm beeped at 3.30 am. There was movement outside our window. Groups had started their ascend towards Base Camp. Ganesh, Jeevan and I got our act together swiftly and we were up on the dark trail with headlights and layers of clothing in a jiffy. It felt like -2°C. The winds howled mercilessly but the faithful Moon lighted our path, enough to aid us through. We walked with the clouds, along the clouds, and in the clouds. And when we got to the viewpoint just after an hour, it was up close and personal with Annapurna South, Gangapurna, Hiunchuli and the magnificent Machhapuchhre.

We waited with the wild wind curling, teasing our spirits. The ball of fire sizzled on the horizon, smearing its rays between layered pavlova clouds. Rain clouds and snow clouds toured with the wind, transmogrifying the skyscape at every minute. It is known that weather changes swiftly and unpredictably in the Annapurna.

Up there, the air inhaled was piercing. It flowed through the nostrils and chilled up the passageway, the lungs. And something, something stirred in the body. A twitch, like the first breath of dawn. Senses alert, I could feel the ether, feathery and alive, all around. It wasn’t just out there—it was a part of me, running through my veins, under my skin. For a moment, everything stopped. Time stretched thin, and the edges of things blurred and softened. It was like being caught inside a Turner painting, where the sky melted into mountains and the mountains bled down into the earth, all of it swirling in oneness. The blazing rays washed across the horizon like watercolours, beaming through cloudscapes that hung like the backs of mountains in the sky. It stirred a deep, aching sense of wonder, a longing so fierce it felt like pain. And there, in that moment, the scene etched itself into my mind, an indelible impression, marked as if by fire. Each second hanging heavy. A pause. And as I finally exhaled, I felt it and know it. The profound realisation, like a revelation—that I was a part of it all – bound and inseparable from sky, earth, and of life itself.

We trek down back to High Camp to meet up with the boys and Ting, and to fuel up on a Nepali breakfast of Tibetan bread, boiled eggs and chickpeas. All packed and bottles filled with water, we descended to Low Camp and headed steadily towards Siding, hoping to get back to Astam by dusk. That amounted to approximately 12 hours of trekking and warranted calf seizure for the following days.

Imagine a crab locomoting sideways down the stairs, as they do. We seem to have acquired the tendency to do so. Give your calves, that singular muscle, a 3-day bash and shock. The retaliation is non-cooperation. Calves recoil and voluntarily disconnect themselves from the neural network after descending from sky to earth.

All said and done, the trek would not have been complete without the presence of superwoman Ting. Ting had come to stay with us for a couple of months at Swara. We had a handful of groups visiting, and once the deed was done, Mardi Himal called out louder than ever. G and I felt physically lethargic. Big A and Little A needed screen breaks. We had a generous gap in the calendar. Ting had dreams of trekking the Himalayas. Her eyes lighted up and her spirits soared when we mentioned the possibility. What was left doing then, was to just do it.

Ting initially thought that a four-legged creature would help her get there. So one was organised for her. On that faithful morning, she started on a mule from Dhampus. 30 minutes in, and having to secure herself with only her right hand on an elevated stone trail, she decided she would rather walk her way, which she did! She was the epitome of steadiness, courage, and mind over body. She overcame her physical limitations and broke the preconceptions of norms. She unknowingly became an inspiration for us to traverse beyond our thresholds, our boundaries, our fears.

Ting suffered from right cerebral infarction (stroke) 2 and a half years ago. She woke up one morning and realised that her left side of the body was paralysed. She recovered over time but not fully. She walks with a limp and the neurons in her left hand and fingers have yet to reconnect with the neural system.

‘Why do people pay for hardships?’ Big A begs the question pleadingly at the starting point.

‘Life seems like an infinite walk.’ Little A wailed on the 2nd day.

These questions leap out, making their demands.

There’s a promise of something beyond comfort—a taste of freedom that can’t be bought any other way. When Big A asks the question at the starting point, it feels like the voice of reason, wondering why one would choose struggle, exhaustion, and uncertainty over the familiar ease of daily life. “Life seems like an infinite walk,” Little A wails on the second day, a sentiment anyone who’s undertaken a challenging journey can relate to. It’s an endless stretch forward, often without a clear destination, driven only by the steps in front of you.

Yet, that is precisely the allure. What may seem like forced labor to some is a form of liberation to others. It’s a chance to break from routines and expectations, to answer an inner calling for something more profound. There’s a beauty in embracing discomfort, in surrendering to the unknown, in testing one’s endurance and resilience. This kind of challenge strips life down to its essence, connecting us to our basic instincts and reminding us of how small, yet vibrant, we are in the grander scheme of things.

So, we choose these hardships to satiate a deeper curiosity, to nudge at our limits, to walk beyond known borders and in some way, feel more alive. The world becomes less ordinary, more awe-inspiring, in each small victory over pain or fear. In choosing these struggles, we may find not confinement, but freedom—a freedom born from the knowledge that we have glimpsed something more in ourselves and the world. And that, in itself, can be worth every hardship.