Who that cares to know much about the history of pumpkins, those voluptuous enigmas of the garden, and how that mysterious squash behaves under the experiments of Time, has not pondered on the life of Mr Kodo. To speak of Mr Kodo, as he was called in his sleepy village of Astampkin is to gather the strange tale of a man whose singular obsession with pumpkins revealed both grandeur and absurdity of human endeavour.

Born to modest circumstances, Mr Kodo, known for his serene composure and curious habit of meditating amongst his vines, displayed from an early age, a remarkable affinity for the peculiar vegetable. He would declare that the pumpkin, with a solemnity, is a vessel of mystery.

Mr Kodo devoted his days and nights to the cultivation and study of pumpkins. Bordered on obsession, he tended to his patch with diligence, documenting every quirk of growth, texture and shade of orange that the sun might bestow. He spoke of the pumpkins as though they were sentient beings, their lives entwined with his. When asked why such attention is on a vegetable, he would reply, “The truth of life is written in their seeds.”

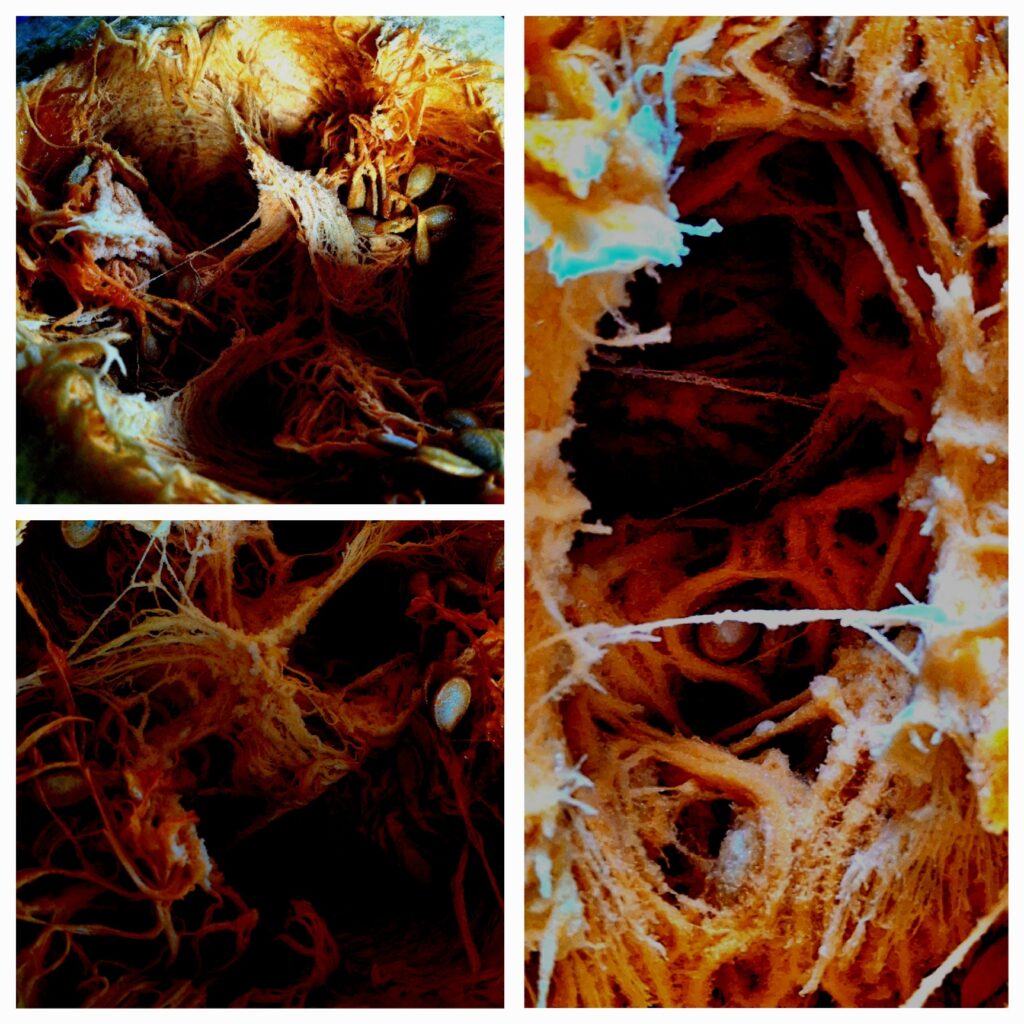

Time played on Mr Kodo and his pumpkins. Seasons passed and his humble patch grew with unnatural vigour. The vines twisted like tendrils of some ancient sea creature, creeping not just across his land but into his dreams. The largest, fondly named Machhapuchhre, weighed more than his buffalo and was said to glow in the dark disquietly under the full moon. Children whispered that Machhapuchhre held magical powers. Others scuffed and said it was merely phosphorescence – a diffusion of light, not divinity. Who would have guessed that his pumpkins were fed with buffalo dung and bioluminescence proteins extracted from fireflies.

It is said, according to the village folks of Astampkin that Mr Kodo’s culinary experiments with pumpkins defied the laws of nature.

He simmered their flesh with rare wild herbs, deep tangled roots and seeds of unknown origin that pulsed with unnatural energy, crafting broths so otherworldly that those who drank it found their faces twisted into ghastly grimaces – and stayed locked that way. He fermented their pulp into bronze bitter syrups that, when consumed, made Time fractured for the consumers, replaying their worst memories in their heads like a broken record trapped in an endless loop. On a particular sinister day, he concocted a pumpkin soufflé that was so delicate it collapsed at the faintest sound of a cry – he called it The Wailing Cloud, and it was said to carry the essence of the unborn harvested from seeds that had never known the warmth of the earth. Those who ate it claimed to hear the song of the dead.

Through all the bickering and scornful advice he acquired from all around him, Mr Kodo’s obsession only deepened. He was convinced that within the flesh of the pumpkin lay the answer to a question no one dared to ask.

Over the years, his squashes grew larger and more grotesque. One was a monstrous orb said to smoulder when the moon was full. Another erupted one stormy night with a sickly reek that could not be extinguished.

As the years passed, his patch consumed that land, and the village seemed to warp under its influence. When Mr Kodo finally disappeared, some say swallowed by a voracious vine, his patch remained. The pumpkins grew wildly hideous and sinister, filling the air with a language no one dared to interpret. For those who lingered, it was clear that the life of Mr Kodo was not a story of a man, but of the mysterious squash that had claimed him.

And so, as the years went by, stripped of flesh and blood, Mr Kodo’s legacy endured.

His mysterious absence silently continued to transmogrify into a sinister vinescape. Where time had long since stopped and the air seemed to wail, the children of Astampkin, the last remnants of a shattered lineage who had scarcely remembered Mr Kodo, grew into a generation bereft of their elders. Ruined as it may seem, the pumpkins ruled Astampkin with an intoxicating air of raging cinnamon, fuming ginger and aggrieved nutmeg, sickly sweet yet suffocating, a mockery of what once brought comfort. The cursed children, their skin sallow and yellow, and bones brittle, laboured under the demands of their orange overlords. Their singular purpose was clear: to cook, serve and ultimately worship the pumpkins in all their grotesque glory.

They toiled ceaselessly, disintegrating with each passing day and feeding the insatiable hunger of the void. And while they cook nothing but pumpkin for the cannibalistic overlords, a haunting song wafted through the air, replaying infinitely like a sacred hymn in a place of worship, its words etched themselves deliberately into every brain cell of Astampkin’s children, becoming an inescapable mantra:

“Send a heartbeat to the void,” the boy chef muttered, stirring an ill-stained pot of Mr Kodo’s archaic pumpkin broth. The void, of course, was the endless demand for new pumpkin delicacies. The children had to relive their memories that had come to pass – bread, cakes, soufflés, pies, soups, broth, porridge, rice, risotto, tortellini, ravioli, lasagne, noodles, pesto, hummus, curries, chillies, chutneys, pickles, momos, ice-cream, smoothies – all variations on the same theme. For now, they stood alone, the world around them lost and blown, their creativity as hollow as the pumpkins their Western cousins used to carve.

“Is it bright where you are?” one girl asks a boy, staring bleakly at a steaming tray of steamed pumpkin momos. “Have the people change?” the boy chef muttered again, this time to the vegetables themselves.

In the darkest hour of their culinary enslavement, a pale pumpkin was delivered from the last of a line of last. Yet, as its flesh was sliced and pureed, the kingdom came crashing down, undone by the black hole of monotony. The village children, now masters of nothing but their despair, created dishes of recoil and disgrace, endlessly feeding the beast their own tender kind. Their torment, immortalised in pumpkin.

Their only solace? The knowledge that the pumpkins would consume them one day, freeing them from their culinary plague.

However, as fate has it, the children were not destined to live in torment for the rest of their lives.

From unknown whereabouts, a wandering mendicant entered Astampkin. His skeletal frame, clad in a tattered doti, seemed fragile against the oppressive air of the village. He paused where the children laboured under the gaze of their orange tyrants, carving, steaming, frying, mashing and serving with empty eyes. The scent of unforgiven toil clung to the air, thick and suffocating.

He observed in silence, his gaze lingering on the largest and most grotesque pumpkins, squatting like bloated monarchs in the filth. Their skins, a sickly orange veined with moss, seemed to pulse with malice. They were not merely vegetables. They were the heart of the curse, the nucleus of all that had gone wrong.

Without a word, the mendicant bent to the earth and began gathering wild grasses from the fringes of the village. His fingers moved deftly, weaving the blades into ropes so tight they hummed with tension. The children watched him with wary eyes, unsure whether to hope or fear.

The mendicant strode towards the void where Machhapuchhre reigned, his steps deliberate and unyielding. He looped the ropes around the larger of the gourds, its bulbous surface glistening with a foul sheen. It resisted, or so it seemed, but the mendicant’s hands were unrelenting. With a practised knot, he bound the pumpkin and hoisted it high, attempting to hang it.

Sensing his intentions, the vine struck like a serpent, coiling around the mendicant’s legs with a desperate, vengeful force. Its tendrils, thick and gnarled and thorny bit into his skin. The mendicant did not falter and dragged the writhing vine with him. The surrounding vines, alerted, pulled at his legs, attempting to root him to the ground. They hissed through the damp air, their thorns tearing into his flesh. Blood trickled down his shins but his hands remained steady, weaving rope after rope from the wild grass he had gathered, each strand taut and unbreakable.

He reached the heart of the curse, glistening with menace. The air was sickly with oppressive decay and a violent odour. The vines lashed and writhed, their tips snapping like whips against his legs and arms.

Finally, he looped the ropes around the base of Machhapuchhre, the monstrous one, its surface rough and swollen with unnatural bulges. He pulled the knot tight, ignoring the hiss of the vines and hoisted it into the air, its grotesque form twisting and contorting as it dangled from the truss of a roof. For a moment, the vines recoiled, their energy faltering. But only for a moment. They redoubled their assault, twisting higher, wrapping around his torso.

Still, the mendicant did not stop. One by one, he bound the pumpkins and strung them up, each effort met with increased resistance from the vines. His body bore their marks—cuts, scratches, and bruises blooming across his pale skin—but his spirit was unwavering.

The sun’s rays finally broke through the heavy clouds and fell upon the suspended gourds. Stripped of their dark dominion, they no longer pulsed. They hung subdued, their malevolence seeping away into the air. One by one, the mendicant repeated his ritual, stringing up the pumpkins until the roof was a gallery of dangling tyrants.

As the last knot was secured, the vines loosened their grip and began to retreat, slinking back into the earth like defeated serpents. The pumpkins, in sunlight, began to change. Their unnatural forms softened, their raging ochre dimmed, and their twisted features smoothed into something almost ordinary.

The children began to stir, their movements less mechanical, their eyes blinking away the fog of monotony. A strange wind swept through Astampkin, carrying with it the scent of grass and freedom, as if nature had reclaimed what was hers.

“Now,” he said, his voice calm, “let them hang in the light like chandeliers. See what they become when no shadows protect them.”

The children did not respond at first, but slowly, one by one, they began to smile as though they had forgotten how. The pumpkins swayed silent and subservient, reduced to the quiet vegetables they were meant to be.

But as the mendicant turned to leave, the pumpkins began to pulsate as if reviving a beating heart. A low hum followed. Then a tremble. And an angry shake.

One by one, they split open with a wet, sickening crack, spilling not seeds or pulp, but dark writhing shadows. The ominous shade materialised into forms—sinister, putrid, odious. The pumpkins had not been subdued; they had merely been waiting.

The mendicant turned back, his eyes betrayed a flicker of sorrow. “I did what I could,” he whispered. “But some darkness cannot be undone.”

The oldest child looked up at the mendicant and asked, “What does it mean, these words – the truth of life is written in their seeds?”

Notes: Phrases in bold and italics are inspired by the song – The Beginning is the End is the Beginning – by the Smashing Pumpkins.